AUGUSTA (Day 2 - part 4)

Old Fort Western is the country's oldest surviving wooden fort which still stands today. We checked in at one of the corner blockhouses and waited briefly for our guide to arrive. Greg was dressed in period attire. We then set out to explore the old fort. It was getting really hot out already.

History:

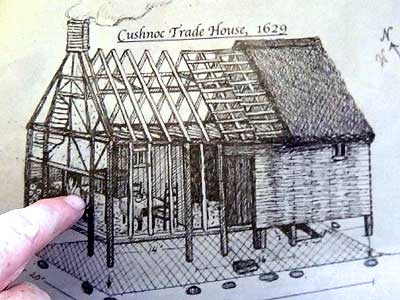

1628 - 1654: Cushnoc Trading Post

The word Cushnoc means "where the current overpowers the tides," with this spot on the river being located 50 miles from the coast. The trading post was run by English colonists from Plymouth, Massachusetts. They mostly traded for furs with bands of the Abenaki nation. It was closed in 1654 since the fur trade was on the decline and the structure burned down in 1676. Excavations of the area have identified the outlines of the old buildings and wall. Tobacco pipes, glass beads, ceramics and hand-forged nails were also uncovered.

1754 - 1767: Fort Western

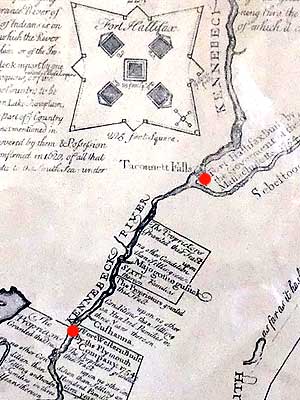

After the trading post closed, this area remained very turbulent. War and fighting over land rights were abundant. There were also threats of a French and Indian invasion. In order to promote settlement in the area and help Britain gain power in North America, the province of Massachusetts decided to build Fort Halifax in 1754 at Teconnet Falls (in Winslow), upriver from the main colonies.

Unfortunately the Kennebec River became too shallow for large supply ships after Cushnoc (Augusta). Another fort had to be built as a storehouse. And so Fort Western was also built, 17 miles south of Halifax. Supplies were shipped up from Boston, unloaded here, and then transported upriver in flat-bottomed boats when water levels rose. This was no easy task. There could be enemy attacks from the shoreline and in some spots the boats and supplies would have to be carried over land.

24 men were stationed here (there were 85 - 100 men at Halifax). Their job was to defend the fort, complete boat repairs, and store and send on the supplies. Much of their time, however, was spent doing the daily routines of cooking, baking and getting wood.

By 1759 the threat of war had greatly reduced when the English captured Quebec. After the war ended in 1763, the fort remained active for a while until it was decommissioned in 1767. For the first time, the area was not such a dangerous place and settlers began to flood in.

1767 - 1850: Howard store and home

From 1755 - 1767 the fort was under the command of Captain James Howard (1702 - 1787). After the last of the troops had been discharged, Captain Howard purchased the buildings and about 900 acres of surrounding land for 270 British pounds (around $500). Together with his two sons, William (1740 - 1810) and Samuel (1735 - 1799), they remodeled the fort into a house and trading post.

William and Samuel ran the S & W Howard store and blacksmith shop out of the south end. William, his wife Martha and their five children lived in the north end. Samuel, a sea captain in Boston, remained there and acted as a broker for goods. The store grew in size and in 1784 was moved to a larger space down the road.The store operated until the Embargo of 1807 (an act that prevented trade with the British) forced them to close. William died in 1810 but the Howard family continued to live here until the 1850s.

1850 - 1920: Tenement House

As more and more industry came to the area, the large building was sold and converted into a tenement house for Augusta’s mill workers. It was broken up into eight apartments. By this time, the neighborhood had become a dangerous place.

1922 - present: museum

The tenements lasted until 1919 when the buildings had become so deteriorated that they were deemed unlivable. To save the old building from eminent domain, the Gannett family (descendants of Captain Howard) bought it and began restoring it to its original use as an 18th-century trading post. In 1922 the fort, along with two newly built blockhouses, was donated to the city of Augusta and opened as a public museum. In the 1980s, archaeological digs unearthed over 17,000 artifacts, some dating back to the 1620s.

The visitor center blockhouse ... square nails

The shape of a nail helps determine the age of a building:

prehistory - 1800: Hand-wrought nails had to be forged individually by blacksmiths. The process was very slow and nails were expensive.

1790s - 1914: Cut nails were mass-produced by fast, automated machines which cut them from sheets of iron. They are also called square nails because of their rectangular cross-section shape.

1880s - present: Round wire nails were much cheaper to produce although they had less holding power than cut nails.

Interesting note: In the 1770s, England was the largest manufacturer of nails in the world. Since nails were expensive and difficult to obtain in the American colonies, abandoned buildings were sometimes deliberately burned down so people could recover the precious nails from the ashes. In Virginia, a law even had to be created to stop people from burning down their houses when they moved.

This is a replica of a 32-foot batteau (French for flat-bottomed boat) that took six men to row and one man to steer. It could carry two tons of barrels and one cannon.

It was waterproofed and preserved with pitch (hot tar) ... and every winter when they couldn't use the boat due to the frozen waterways, they would unplug a large hole in the bottom of the boat to sink it. This protected it from damage caused by surface ice (where the constant freezing and expanding of the ice could crush it). Wooden hulls were designed to remain wet, so if they brought the boat ashore, it would dry out, contract, and cause the seams to open up. This would cause leaks in the spring when the boat was relaunched. In the spring, the boat could be brought back to the surface, pumped out, and made ready for another shipping season.

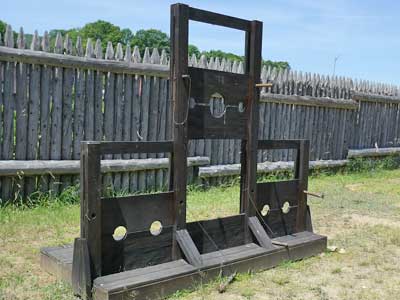

The stocks

The powder magazine was an 18-foot-deep storage unit for gun powder. This was meant to limit and contain any accidental explosions. During an 1983 excavation, the magazine's old footprint was found. This structure was rebuilt on that location.

A pulley system with a hook was used to raise and lower the powder barrels. It was critical not to create any friction or impact that could create a spark and ignite the volatile black gunpowder. Rolling, dragging or dropping a barrel could spell disaster.

Powder kegs awaited shipment to Fort Halifax.

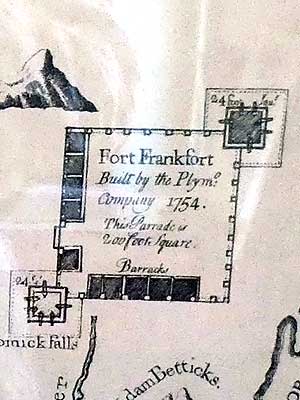

Two blockhouses (24 feet square in size) were positioned at opposite corners of the fort. Their high elevation gave a view of the river for more than a mile.

Unloading supplies from the ships from Boston

Taking the bateaux up to Fort Halifax. Attacks from the shore were not unheard of.

We walked upstairs...

Although the fort was never directly attacked, they were prepared. Each blockhouse had several 4-pound cannons.

A 1-pound cannon ball was about the size of a golf ball.

A 4-pound cannon ball required 1 pound of gunpowder.

The lanolin found in sheep skin helped preserve the metal. ... This naval cannon had a 1 mile range.

Cannons had views of the fort...

... as well as the river.

(right) Bar shot was used to attack the masts and sails of ships. When fired, this would create a spinning motion that could destroy anything in its path.

Chain shot was similar to bar shot but without a solid bar ... Grape shot was a collection of smaller-caliber shots packed tightly together in a canvas bag. When fired, the projectiles would scatter in all directions (like with a shotgun).

Greg demonstrated the loading and firing of a doglock gun replica. The 'dog' was an external catch or lock that acted as a safety feature by preventing the cock from striking the flint. Older flintlock weapons could easily misfire (known as a flash in the pan) or accidentally discharge when in the 'half-cocked' position (where the hammer was partially pulled back but not fully engaged for firing). This was a much safer way to carry a loaded weapon. By 1720, the British were no longer using doglocks. Later flintlocks contained internal safety parts in the half-cocked position.

The doglock is engaged so the weapon is safe to load.

It was vital to keep the gunpowder dry. Damp gunpowder could fail to ignite properly, causing the bullet to lodge in the barrel and create a blockage. If the shooter fires again, the barrel could explode.

This is a muzzle-loading rifle, meaning the powder, wad, and a lead ball are placed into the barrel and then pushed it all down with a ramrod (stored on the side of the barrel)

The doglock becomes disengaged as the cock is moved to the full-cock position. The trigger can now be pulled to fire the gun.

Back outside...

This space between the two tall fences was known as the killing field zone, should any enemy solder get trapped in there.

We then entered the sturdy 100 by 32-foot main house. This is the only original piece of the fort to survive.

An exhibit room

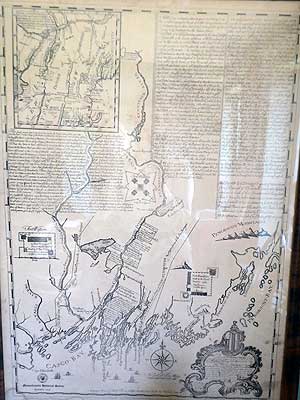

A map ... showing Fort Western (lower red dot) and Fort Halifax (upper red dot)

During the 1700's, four forts were constructed on the central Kennebec River to secure English claims to Maine's eastern frontier and promote settlement. Fort Richmond (1720 - 1755) was the first.

Fort Frankfort (1752 - 1759) was renamed Fort Shirley and served as the first stop of the supply chain to Fort Halifax. It was rarely manned. In 1760 most of its buildings were torn down and used to construct a court house. The town was renamed Pownalborough.

A model and drawing of the Cushnoc Trading Post

return • continue