ACADIA NP (Day 4 - part 1)

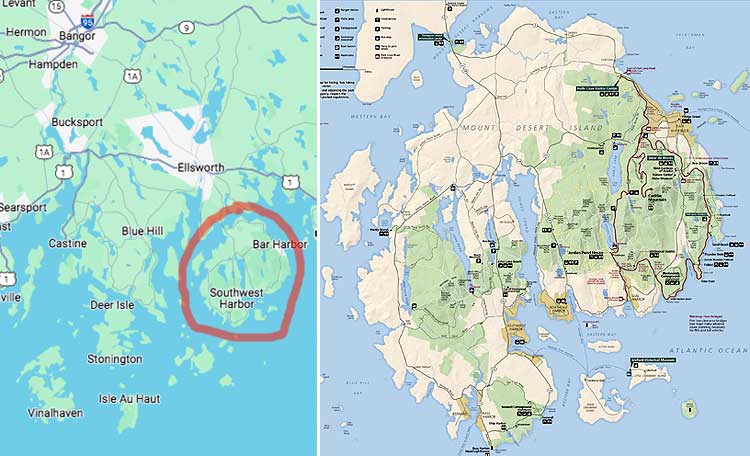

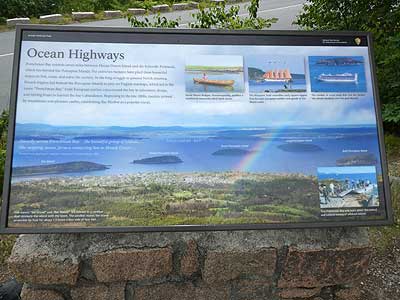

After our lovely buffet breakfast, we drove to the Hulls Cove Visitor Center at the entrance of Acadia National Park.

I got addicted to the hot egg-cheese-muffin sandwiches.

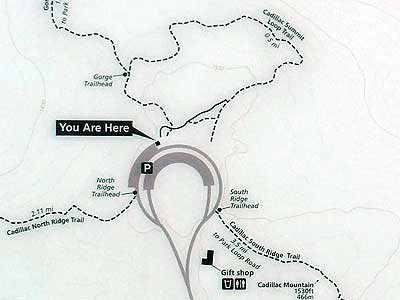

There was ample room to park in the large lot. We walked up the long set of stairs to the visitor building, grabbed a map of the park, talked with a ranger about various hiking trail options, then returned to the car. We then set out for Cadillac Summit where I had reserved us a timed entry of 10 am.

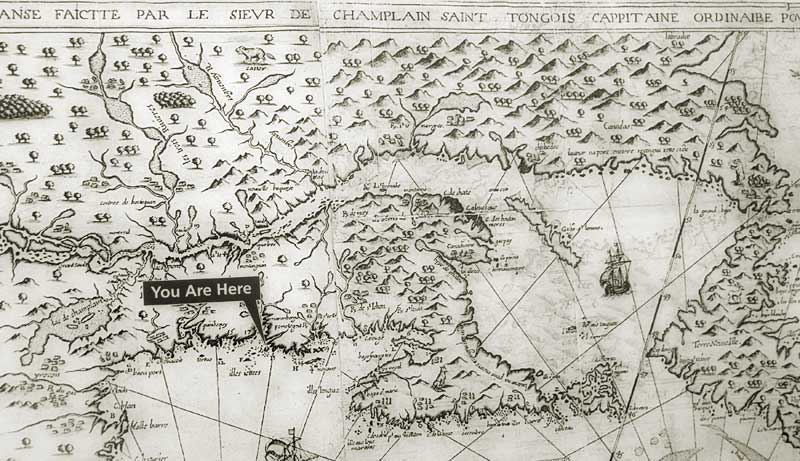

Originally, this area was inhabited by the Wabanaki (People of the Dawn). In 1604, while mapping the North Atlantic coastline, French explorer Samuel Champlain (1567 - 1635) recorded his observations and named Mount Desert Island. For the next 150 years, the French and British fought to control this territory. Once it fell into the hands of the newly formed United States, people began establishing settlements on the island. In the mid-1800s, tourism arrived. Enormous hotels and extravagant summer homes soon transformed the small farming and fishing villages.

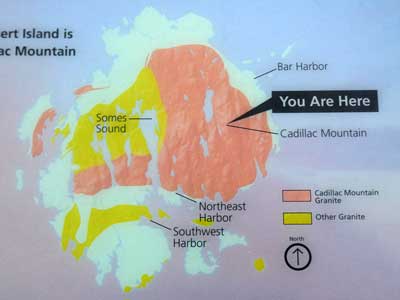

The park was first set aside in 1916 as Sieur de Monts National Monument. It was expanded and became Lafayette National Park in 1919 (making it the first eastern national park) and Acadia National Park in 1929. Today it preserves about 38,000 acres, 65 miles of coastline and 20 islands. It rises from sea level to 1,530 feet.

The word Acadia comes from the word Arcadia, a term used by Giovanni da Verrazzano (1491 - 1528, the first European explore to sail the Atlantic coast between Florida and New Brunswick in Canada in 1524) to describe the Atlantic coast. He based it off the Arcadia region, a peninsula in southern Greece, which was seen as an unspoiled, harmonious wilderness.

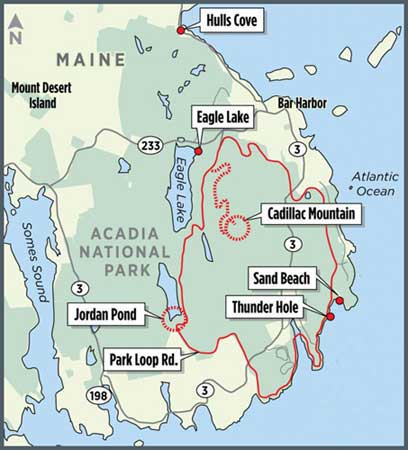

We drove down Paradise Hill Road and stopped briefly at an informative overlook.

Overlooking Frenchman Bay. The bay extends seven miles between here and the Schoodic Peninsula. French frigates used to hide behind these islands to prey on English warships.

The arrow points to the town of Bar Harbor.

#1 - Bar Island with its land bridge that gets revealed during low tide

#2 - Sheep Porcupine Island

#3 - Bald Porcupine Island

The big land mass in the distance is Schoodic Peninsula.

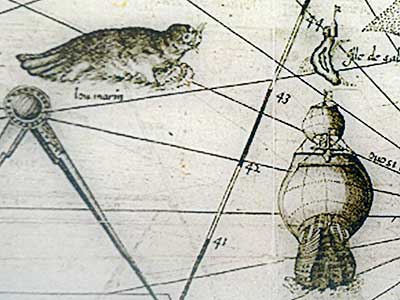

Samuel Champlain created this "Map of New France" in 1613. It follows the coastline from Cape Cod up to Canada and westward to the Great Lakes.

It included critters of the sea ... and land (clearly a raccoon!)

There was only one car ahead of us at the small Cadillac Summit entrance station, but up top, parking was packed. We circled the small lot three times until we came across someone leaving... otherwise would have had to drive quite a ways down the hill to a lower lot then walk all the way back up the very steep street. Besides, given the line of people walking up the hill, there were no guarantees there would have been parking spots down there either.

Looking down on Eagle Lake on the drive up

We walked the half-mile loop trail. The place was packed with people. While the view was indeed lovely, it was rather hazy out.

Cadillac Mountain honors Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac (1858 - 1730), a French explorer who received this area as part of a large land grant from King Louis in 1688. The French were eventually defeated by the British in the mid-1770s at Quebec.

The island is high and notched in places so that from the sea it gives the appearance of a range of seven or eight mountains.

The summits are all bare and rocky... I named it L'Ile des Monts-deserts.

- Champlain, 1604

Bar Harbor and some of the Porcupine islands

A cruiseliner ... The Margaret Todd resembles early square-riggers that brought European settlers and goods to the Maine coast.

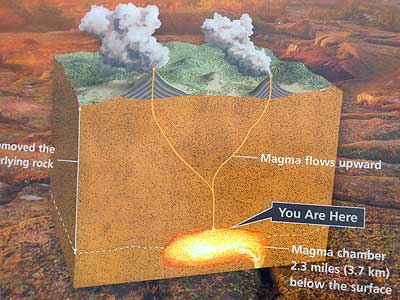

Cadillac Mountain formed millions of years ago when a very hot liquid cooled deep below the Earth's surface. Trapped in a magma chamber more than two miles deep, the liquid crystallized into pink granite. Eventually erosions and glaciers removed the softer, overlying rock, revealing the harder, more resistant granite.

(right) Looking down on Otter Cove

We returned to the rental car and drove back down the hill. As we exited, we saw the SUPER long line that had formed to get in at the small mountain entrance station. We returned to the visitor center, hoping to park and take the free shuttle. There was not only no parking, but tons of cars circled about. We realized that was not going to be an option. Not to mention, if it was bad here, it was going to be even worse inside the park. So instead, we decided to go to a completely different part of the island that the ranger had recommended to us in the morning.

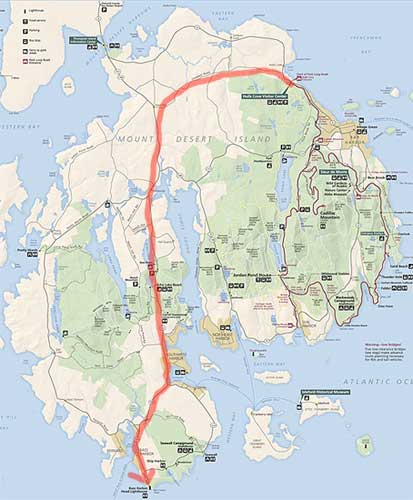

Our drive across the island, from Hulls Cover down to Bass Harbor

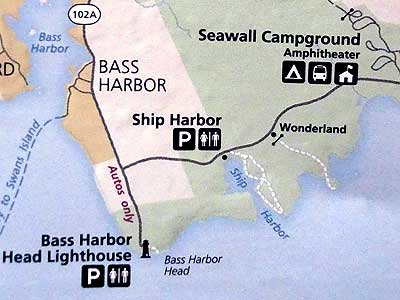

As we approached the Bass Harbor Head Light, we got stuck in a long line of traffic. It was a narrow, two lane road so we couldn't turn around. Unfortunately we couldn't see what the problem was either. So we just waited, creeping forward ever so slowly. Eventually we discovered that it was a super, tiny parking lot. Only when a car left, could one from the line would take its space. Eventually it was our turn.

We started with the Tower View Trail to the lighthouse.

Maine has more than 70 lighthouses along over 3,400 miles of rugged coastal shoreline. They have worked to keep mariners safe since the 1800s. Back then the ships carried granite, lumber and fish. Today it's more lobster and tour boats.

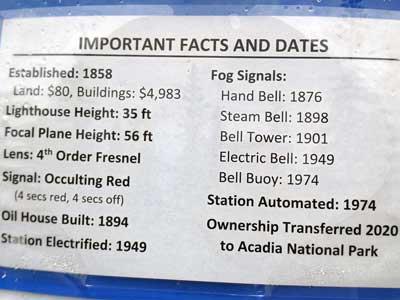

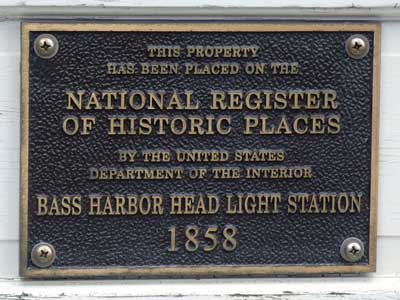

Built in 1858, the two-story dwelling was connected to the lighthouse by a 21-foot covered passageway. This allowed the keeper to attend to the light at night without having to go outside, especially during cold, windy winters.

When thick fog crept along the coast, sailors were often unable to see the light. So a bell was used. The Bass Harbor station signal was one stroke every 10 seconds. Today, a nearby bell buoy performs that function today. We could actually hear its rhythmic clanging out on the water.

Originally, keepers had to light the beacon each night by hand. The lighthouse was electrified in 1949 and fully automated with a light sensor in 1974, when the last keeper left.

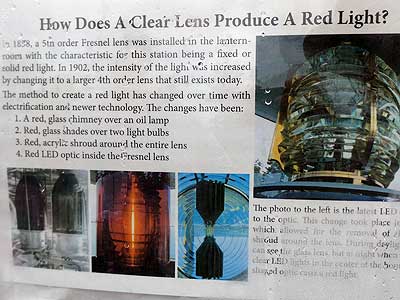

The original lens installed in the lantern room in 1858 was a 5th order Fresnel lens. It was a solid or fixed red light. In 1902, it was upgraded to the larger 4th order lens where the red lights occults (darkens) every four seconds.

Each light has a unique light pattern and color, allowing sailors to identify their location. For example, Baker Island Light (1828) is a white light flashing every 10 seconds. Bear Island Light (1839) is a white wight flashing every 5 seconds. Burnt Coast Harbor Light on Swans Island (1872) is a white light occulting (hiding) every four seconds. Egg Rock Light (1874) has a red light that flashes every 5 seconds.

Originally it was just red glass over an oil lamp. Today there is a red LED optic inside the lens.

return • continue