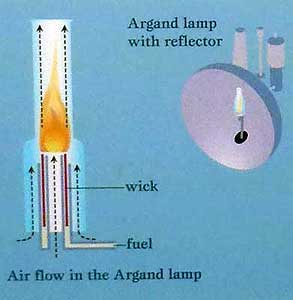

Since ancient times, bonfires, braziers (fires in buckets) and open-topped light towers have guided and provided safe passage for mariners by identifying port entrances and helping ships avoid dangerous reefs and sandbars. Before electric lamps, people used wood, coal, dried vegetation soaked in tar, sperm whale oil, animal fat, and eventually kerosene (which caused other problems such as heavy soot and the need to frequently trim the wicks). Of course open fires were practically useless on rainy and windy nights.... when they were probably most needed.

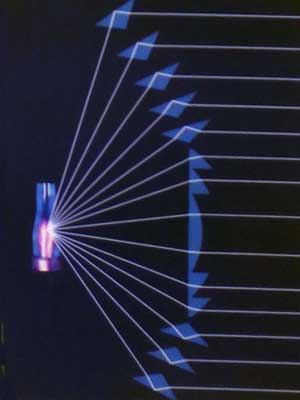

Eventually, the use of strong, smokeless lamps with a steady, concentrated flame were set between polished mirror reflectors and a curved, glass magnifier lens. But even so, over half of the light produced was scattered and lost due to dissipation. Even the most effective lighthouses could only be seen 8 to 12 miles away. So shipwrecks continued to occur with regularity. Somehow, the light had to be "aimed" out in the direction of the sailing vessels.

As early as 1759, thick glass lenses were proposed, but they absorbed too much light and were very heavy. The first lighthouse to use such lenses was in England in 1789, but again, it was mostly impractical.

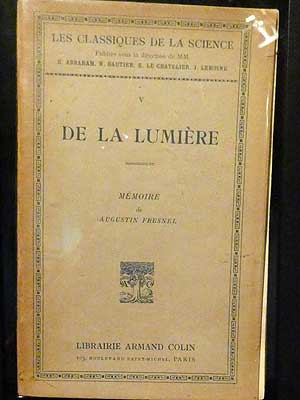

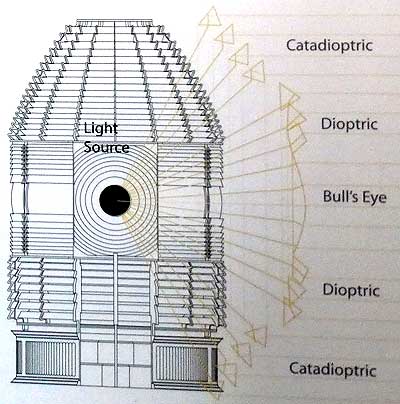

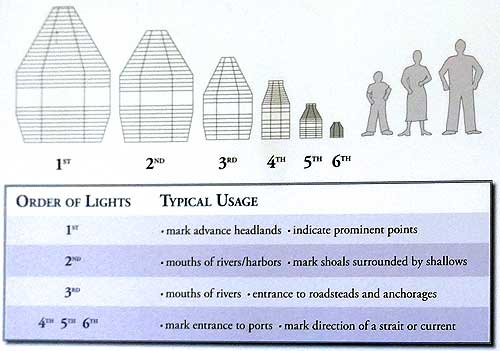

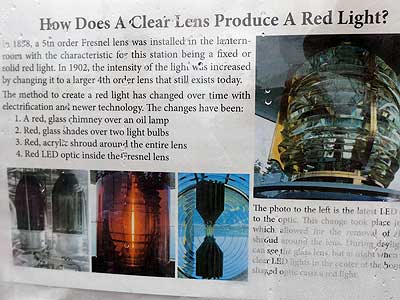

In 1822, French physicist Augustin Jean Fresnel revolutionized lens optics through his understanding of how light behaves and can be manipulated and amplified. A Fresnel (pronounced Freh-nel) lens used separate, precisely cut, glass prisms to magnify and focus light from a single source into a horizontal sheet projected in all directions. This captured around 83% more light than reflectors. Now, the brightest lighthouses could up to twenty-four miles away. The US adopted them by 1841, with all lighthouses equipped by the 1860s, using different orders (sizes) for different ranges.

Augustin Jean Fresnel (1788 - 1827) was a very sickly child and died from tuberculosis at the age of 39.

The lens is a series of prisms that bend and then focus light rays into a concentrated beam before emitting it from the mid-section of the lens.

Lenses are classified by focal distance (the distance from the light source to the inside surface of the lens) into orders. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd order lenses were usually installed in seacoast lighthouses to warn ships that they were approaching land. The 4th, 5th and 6th order lenses were used in harbors and sounds.

A smaller 5th order lens in front of a larger 3rd order lens ... A 2nd order lens measuring 9.5 feet in diameter and weighing nearly 3,000 pounds. It is capable of displaying a 25 million candlepower beam. Here it is only lit to 53 candlepower.

Each individual prism had to be hand-ground and fitted into place.

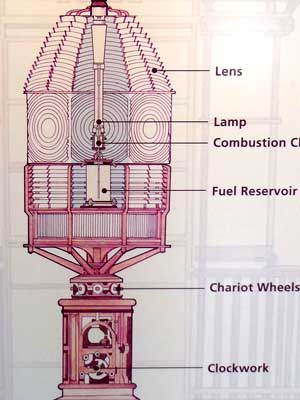

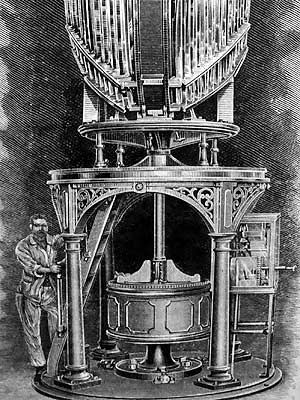

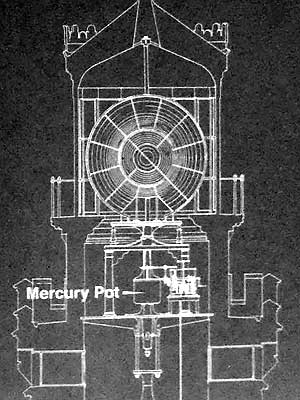

A lamp rests inside a lens which sits inside a protective top. The lens could either be fixed (non-rotating) or flashing (rotating). Many were turned by a clockwork and weights.

Sample bases

Originally, lenses floated in a basin filled with hundreds of pounds of mercury, allowing their heavy assemblies to rotate with almost no friction. Unfortunately this exposed keepers to toxic vapors as they routinely cleaned and maintained these systems, leading to mercury poisoning. Once the hazards of mercury were understood, it was replaced with newer technology.

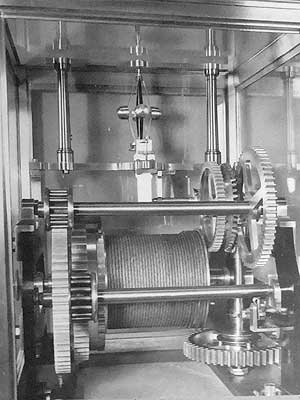

A sample clockwork ... The heavy weights descended by a wire cable (thanks to gravity) and had to be wound back up every several hours.

Despite modern navigational aids, sailors still rely on vision to confirm their position. To assist in telling one from another, lighthouses were given unique characteristics... different shapes, heights and colors, and their lights varied in pattern, color and duration.

Originally it was just red glass over an oil lamp. Today there is a red LED optic inside the lens.

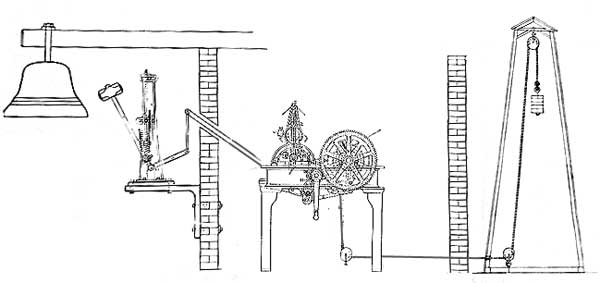

Lighthouses also had auditory aids to warn ships in thick fog, when the light couldn't be seen. This started as cannons, drums or manually rung bells. Eventually powerful, automated horns were used.

Fog horns

Fog bells

The Stevens Striking Machine was an automated bell that was powered by weights in a tower.

Of all the lighthouses in the US, only about half remain. All active ones are automated and few are staffed. Many are replaced by small, lightweight, durable lenses. But in the past, keepers and assistants lived on-site and maintained a strict maintenance routine, regardless of conditions. Roofs had to be repaired, fences and wall repaired and whitewashed, firewood chopped, clothing washed and mended, meals prepared, dishes washed and water hauled from the cistern. Many of the families kept gardens and livestock. In 1939, the US Coast Guard took over all lighthouses and all keepers became members of the military.

Polishing the lens ... The uniform's insignia